We are not poor!

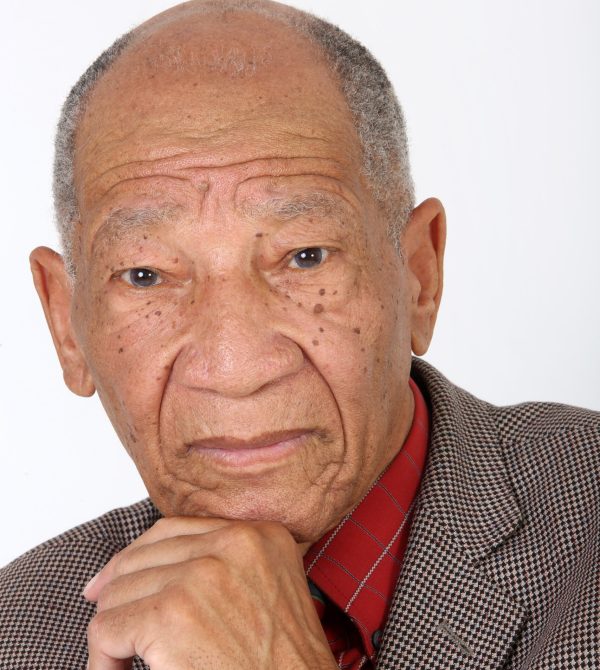

“I am so tired of being poor!” I complained. Unflustered, Dad puffed on his pipe. “We are the only family in this community that does not yet have a car!” My whining became irritating, even to me. Dad exhaled. The sweet smell of Rum and Maple tobacco wafted through our living room.

“Hmmmm…poor…?” The smoke from his Meerschaum pipe spiralled heavenward, disturbed only by the eddies that dictated its trajectory.

“Yes! Yes! Poor! Poor! Poor!” I barked.

“I am prepared to agree that we probably have less disposable income than others in the community.” My adolescent tantrum bounced off him like flat stones skimming off the surface of a placid lake. He mulled what to say next.

“And I am sick of it!” I knew that this level if disrespect could fast-track me into an early grave.

“We have books. We have music. We have art. We have critical and creative thoughts. We have each other. That makes us fabulously rich.” Annoyingly, he made sense! “We may not have as much money as others, but poor? No, we are not poor.” Two days later there was a knock at the door.

“Ready?”

“Hello Uncle Al. Ready for…?”

“Dad didn’t tell you?” My uncle smoothed his Brylcreem hair. “He wants to take you for a drive.” Growing up in Apartheid South Africa, people of colour, like us didn’t “take drives.” We worked. We studied. We went to church. We spent family time together. But most of all, we stayed as far away from the police as we could! Taking “drives?” oh no, oh no, oh no! That is what White people did.

“Oh…Hello Father Monti!” Dad was a priest in the Anglican church.

“I would like you to meet my son, Mrs Petersen. This is Mark.”

“Oh Mark! I am so pleased to meet you! Dad has told me much about you.” She wiped her hands on a battle-worn apron. Her hair had not come into close proximity with a brush for some time. She didn’t shake my hand. She hugged me! “Please come in. I will put the kettle on.” A rat ran past the front door.

“You can’t be serious!” I thought, in total dismay. “Come in…here?” I had just seen a rat run out of the house, and into the filthy swamp!

“Thanks Mrs Petersen. But please don’t go to any trouble on our account. Sorry to drop in on you unannounced.”

“Oh! Nothing is too much for you Father Monti! You know that!” Her rotund tummy wobbled as she chortled with genuine affection for my dad. My Uncle Al had gone a whiter shade of pale. He gave my dad a “Shall I wait in the car?” look. Dad shot back with a “Get your arse in here!” glare that would strip paint of the side of a ship.

Parravlei, a slum, lay cheek by jowl with the township of Kliptown. I call it a “township” because…well I don’t really know why. In Apartheid South Africa, in the 70’s, a residential area for people of colour was called thus. A residential area for White people was called a “Suburb.”

“Please sit. You are very welcome.” Mrs Peterson had an ‘I’ve just won the lottery’ size smile on her creased countenance. Uncle Al scanned the well-season couch with a “Who died in that couch?” look. I responded with a “OMG! Will I be next to die on that couch?” look.

“No sugar for me please.” Dad said. He flopped into an armchair that had seen better days.

“Of course, Father Mo. No need to tell me. You are family.” Uncle Al and I shared out preferences for hot drinks with the level of caution reserved for petting pythons. Mrs Petersen rushed out in a flurry of life-stained skirts. Then, just as quickly, she spun on her heel. She exploded back into the room. “Father Monti, let me put on ‘Grazing in the Grass’ for you. (https://youtu.be/qxXZF60EPdM?si=uybZouRUyzL0c96W) I know you like Hugh” Even I knew she meant Hugh Masekela.

“But how the hell will you do that, Pray tell.” I thought cynically. “…you have no electricity!” She scampered to the other end of the room. There stood a wind up gramophone. She primed it. Moments later, Hugh Masela joined the conversation.

“What your dad doesn’t know about music….huh!” She shot a glance in my direction. “Back in a jiffy.” This bundle of uncontrolled energy stopped again at the door again. “Oh, Don has just published a new poem. I would like to discuss it with you, but let me get your tea.” Don Mattera was a gangster turned journalist, poet and community activist. He then became politically active. As a result of these activities, he was banned from 1973 to 1982.

“Let me help you.” Dad, pushed down on the armrests of his chair.

Mattera was confined to his home. He spent three years under house arrest. He was detained, his house was raided, and he was tortured more than once. During this time, he became a founding member of the Black Consciousness movement and joined the ANC Youth League. Mattera was born in Western Native Township (now Westbury). I knew the area well. This is where I went to high school.

“No Father Monti. You relax.” She handed out mugs and plates. Plates? What for? A barefoot urchin shyly shuffled into the room, balancing a plate of precariously, pyramid-piled, Vetkoek. This is a local delicacy. It is a simple, deep-fried donut-type treat that is universally enjoyed in South Africa. “I’m afraid I don’t have much jam left” she winked at me. “But you can use all there is.” The All Gold apricot jam was a favourite of mine. But how could I take this from her. She read my thoughts “Die Here is my herder.” She quoted Psalm 23, in Afrikaans – “The Lord is my shepherd. I shall not want.” I fought back tears. This woman did not know me. She had absolutely nothing. But she shared it with me.

“Delicious as usual Mrs P.” said Dad.

Uncle Al said “err…yes, thank you.” He was still dealing with his Post Traumatic Stress.

“Now, Father Monti. What do you think of Don’s new work?” Dad paused for effect. He was a gifted orator and an accomplished thespian. He knew how to work a room. Then he started –

“For a cent

Each morning corner of Pritchard and Joubert

Leaning on a dusty crutch

Near a pavement dust-bin an old man begs,

Not expecting much.” Dad’s voice was a mellow marriage of honey and hot chocolate. Every eye was laser locked on him.

Then…

“His spectacles are cracked and dirty

and does not see my black hand drop a cent into his scurvy palm

but instinctively he mutters:

Thank you, my Baas!

Strange, that for a cent a man can call his brother, Baas.”

We whip lashed around. Mrs P had picked up where Dad left off! “But, but…” I spluttered silently. “My dad is a man of towering intellect and erudition!” I continued my internal monologue. “… and you are…well…poor!”

“What do you think Mrs P?”

“This poem, more than others, is so obviously why we call him the Poet of Compassion.”

“I agree. But I sense that you have…”

“Yes, I have some questions. The content is good. But it is more free verse. It doesn’t scan as much as I would like.”

“I think free verse is valid.” said dad. But, raising the notion of ‘Baas’ is very disturbing”

“Of course it is. Don highlights how the Apartheid government has broken us. We are reduced, for the sake of a pocketful of lose change, to calling another man Baas (Master)” Mrs P was now surprisingly animated.

And so they continued. Dad never spoke down to her. He interacted with her as an equal. To my astonishment she responded to his rapier-sharp thrusts with articulate parry.

I have often contemplated this moment. It was on this day, in 1974, in the stench of Parravlei, that in a very real sense, the kARTwe Project was born. I learned a life-shaping lesson. Because someone is poor does not mean that they are stupid. People of limited pecuniary means are not second class intellectual citizens. Over the years I have found this to be wonderfully true in various projects that I have run.

The kARTWe Projects, in Uganda, teaches street kids and slum kids to draw and to paint. Invariably, none of our students has held a paintbrush in their lives. Yes, with coaching and care, they are producing creativity that has lay dormant in their dust covered souls. Now, together, we are united in turning the most notorious slum in Kampala into the biggest open-air art gallery in the country.

No one spoke on the way home. Uncle Al was still in a state of shock. Dad puffed on his pipe. He didn’t say anything. He didn’t need to. I had met a woman whose hospitality and intellect were inversely disproportionate to her monetary value.

I have never since complained about being poor.

One person cannot change the world

but YOU can change the world for one person.